Herbert Fuller Clark: an investigation

by Adam Davies / 26 January 2023

Introduction

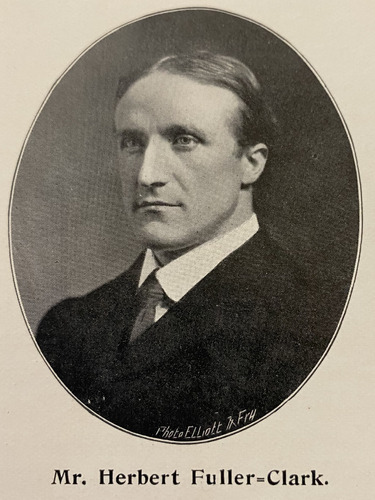

Herbert Fuller Clark (1869-1934) was a British architect working primarily in the Arts and Crafts style. His most famous work is his renovation of the ground floor of The Blackfriar pub in the City of London. It has been termed the "best pub in the Arts-and-Crafts fashion in London" (by Simon Bradley, in Pevsner's Buildings of England guide to the City). A cluster of his buildings in Fitzrovia, centered on the offices of the TJ Boulting plumbing company, has also received some attention.

His work is little known today — practically all of the (few) references to Fuller Clark in later scholarship note his obscurity. Architectural historian Alistair Gray wrote in 1985 that "examples of the work of Fuller Clark are rare and of special interest".

I think his work deserves to be more well understood and more widely appreciated — they are beautiful buildings, speaking to a pivotal moment in architectural history at the intersection of the British Arts and Crafts and Queen Anne styles, the European Art Nouveau, and new materials and techniques.

This article has sprung from two serendipitous encounters: a walk in Fitzrovia on an summer evening after a rain storm past the Candover Street group of buildings and a drink in the Blackfriar pub whilst following Ian Nairn's brilliant London guide, Nairn's London. Both were as enchanting as any architectural experience can be and left me hungry to find more.

Unfortunately, he did not build much, and much of what survives is a real challenge to find. Most of his buildings are in and around London, though with some work scattered as far as Jamaica, where he worked on both his own projects and as a supervising architect for others around 1912. He also won several architectural competitions with projects that remained unbuilt, a fact that led to him serving as President of the Competition Reform Society from 1900 to 1905.

This post articles on research at the British Architectural Library in the RIBA, as well as a host of online resources, especially the Internet Archive. David Pollock, a relative of Fuller Clark, also helpfully provided some details of his life.

I hope this information is useful to the curious. If you happen to know anything else about Fuller Clark, I would be grateful if you could email me.

All photos are my own unless otherwise specified.

Notable works

35 Preston Road, Westcliff-on-Sea (c. 1900)

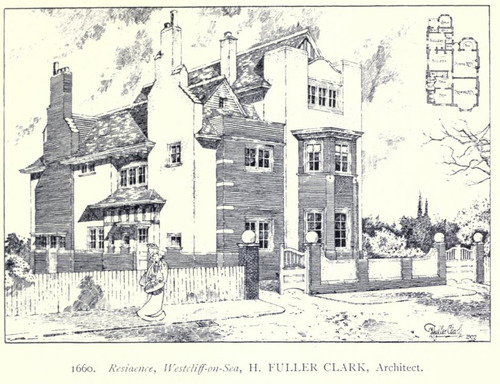

In 1900, Fuller Clark designed a house in the Southend-on-Sea neighborhood of Westcliff. The exact construction history of this building is a bit confused, but the house was probably constructed as a "small residence" for a Mr J Luke Cocks in around 1900, with work starting in January of that year.

The three story house sits on a residential street of large detached and semi-detached homes just north of the railway station and a few minutes walk from the Thames Estuary. It is made of red brick, partially covered in white render. The Buildings of England guide for Essex attributes the house to Fuller Clark and notes that it "combines elements of Arts and Crafts, Voysey, and Mackintosh".

He was evidently proud of the building and later exhibited drawings of the house at the Royal Academy in 1903 under the name Treverne House.

The Blackfriar, Queen Victoria Street, London (c. 1905 & 1921)

The Blackfriar, a pub in the City of London, is the building for which Fuller Clark is best known. Squeezed into a triangular site near the busy Blackfriars station, the pub had been originally designed as a conventional four-story Victorian office building in London stock brick. Over two separate renovations, the first in about 1905 and the second completed in 1921, this Victorian building was transformed.

The exterior was covered in metalwork, mosaics, and sculpture, advertising the ales and brandies available within and introducing the pub's monastic theme. Stonework on the same subject adorn the entrances, both on the triangular tip of the building and around the side door, originally the entrance to the saloon bar. That portal is a particularly striking one, with a step down from street level into a recessed alcove with a door on the right into the building.

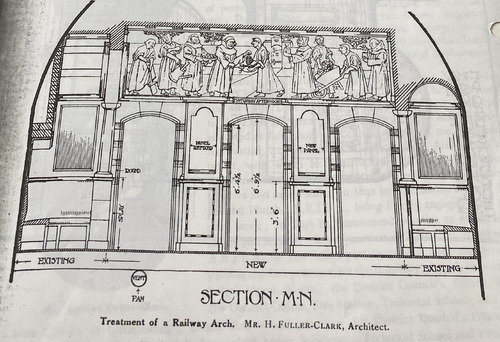

The pub's interior is divided into three rooms: a ladies' bar facing Queen Victoria Street, a saloon on the other side, and a snack bar at the back beneath the railway arches. The final room was the last built, added only in the 1921 renovation.

Much attention has been given to the pub's rich decorations of marble, metalwork, and mosaic. The copper friezes, by Henry Poole, depict scenes of drunk and happy friars. The decoration is most intense in the snack bar, where almost every surface is covered in mirrors or metalwork, creating the effect of a "complete jewel house" (Nicolas Taylor, 1973).

With all that décor by Poole, as well as by sculptor Charles Bradford and other artists, it is easy to overlook Fuller Clark's unique contributions to the space. Ian Nairn's review of the pub in Nairn's London makes this point as well, although I disagree with his general view on the pub — I think it is magnificent.

"This is a late-nineteenth-century equivalent of the Soane Museum, with mirrors and deception everywhere. It reaches a climax in the Snack Bar at the back of the Saloon, with a barrel vaulted alcove in which real views through to the bar are expertly balanced against multiple reflections. It is said to be one of the masterpieces of London, and it would be if someone like Mackintosh had been the designer. But unhappily is tainted with a particularly musty imagination which has clouded the space like a bad pint of bitter. The theme of bibulous friars is flogged to death — each item inscribed "by Henry Poole R.A" — the frieze is crowded with sententious axioms, the walls look like very old gorgonzola. It is not really wild enough, always flirting with Art Nouveau and never really going the limit. When the pressure of friardom lets up the effect is much better and more Art Nouveau, like the little bar on the corner."

Regardless of views on the merits of the decoration, it is undeniable that much of the magic of The Blackfriar lies in Fuller Clark's architecture — the elegant treatment of the low, claustrophobic railway arches, the lightly sinuous work around the windows of the ladies's bar, and the play of interior and exterior around the entrance to the saloon.

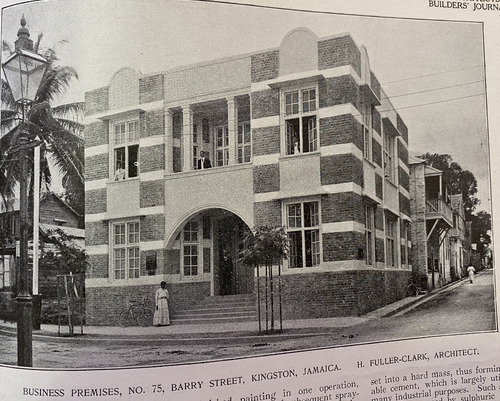

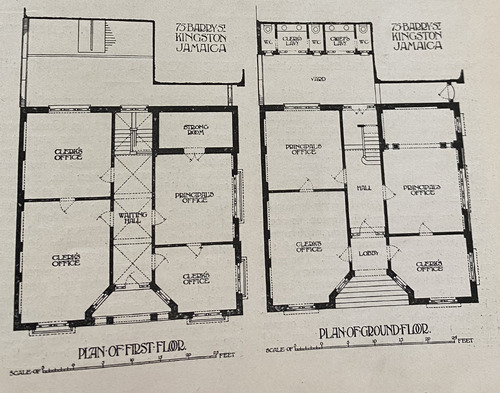

75 Barry Street, Kingston (c. 1912)

The most notable building that Fuller Clark designed in Jamaica, which unfortunately does not appear to survive, was a two-story office in central Kingston. Built around 1912, the upper floor housed the Jamaica headquarters of the Gresham Life Office, a London-based insurance company. It was faced with local red brick and cement bands, and built with reinforced brickwork, evidently required by the building authorities in the wake of the 1907 Kingston earthquake.

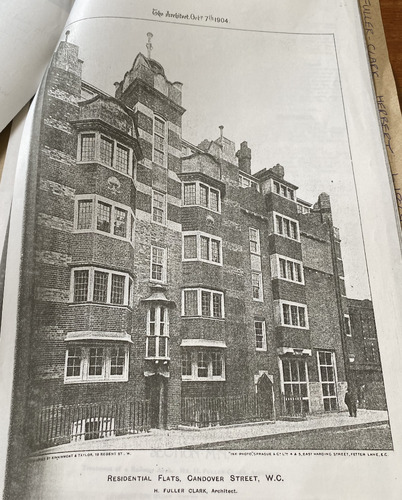

Candover Street development (1898-1904)

After the Blackfriar, the other great Fuller Clark project is a compact cluster of flats and offices around Candover Street in Fitzrovia. Five buildings by Fuller Clark, mostly designed in partnership with others, stand within a two minute walk of one another. They are centered on the offices of T.J Boulting's, a firm of ironmongers and sanitary engineers who developed properties around their premises on the Howard de Walden Estate. At the time, the area played host to the Middlesex Hospital and to a number of small shops and craftsmen to serve the surrounding shops and wealthier residential areas. Since then, like the rest of zone 1, the area has become more well-to-do, and the flagship York House has become an art gallery.

The first structure to be built as part of the development was 40 Foley Street, a five story block of flats, designed in 1898 by Fuller Clark, his long-time partner C.E Hutchinson and Percy Boulting, presumably a relative of the Boulting clan. The facade is faced with brick and white render and topped with two curved gables. The Survey of London describes it as a "up-to-date but not eccentric performance".

In 1899, Belmont House was built on Candover Street itself. Similar in look and feel to 40 Foley Street, it is taller and more lushly decorated. It retains the same distinction in brick color between the ground floor and the first floor, but instead of plain yellow stock brick as is the case on Foley Street, Belmont House has a band of dark, almost black brick. Light Art Nouveau lettering above the door reads the name of the building.

Three more buildings followed on in a single wave in 1903-1904: Tower House, York House, and Oakley House. The former two face Belmont House directly, and the latter Riding House Street, then known as Union Street. These were again designed in partnership with Percy Boulting, but without Hutchinson.

Tower House strongly resembles Belmont House, though with two columns of bay windows and a cute, almost chinoise bay above the front door.

Next door, York House served as the offices of the Boulting firm itself. It has a single column of square bays and a lush green-and-gold mosaic reading:

TJ BOULTING & SONS SANITARY AND HOT WATER ENGINEERS ESTABLISHED 1808

The main office of the Boulting firm faces Riding House Street around the corner and features two more mosaics, in the same style. A sign indicates its year of construction — 1903 — in a stylish Edwardian fashion. Oakley House next door has two columns of square bay windows and a facade of red brick and white render.

The entire development of 37 flats was acquired by a local housing association in 1978 and renovated by architects Pollard Thomas & Edwards in the 1980s for further use as flats. These renovations added new kitchens, escape routes, and much more generous windows. Their lightly postmodern additions are an elegant fit with Fuller Clark's style.

Other works

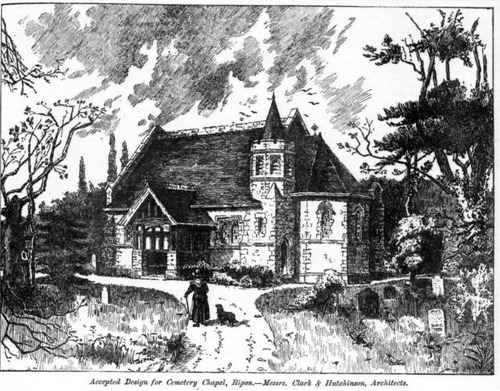

Ripon Memorial Church (1892)

In 1892, Fuller Clark and his long-time collaborator Charles Edward Hutchinson won a contest by the Corporation of Ripon to build a cemetery chapel, though the project was never built, ostensibly because of the architects' fees.

Ilford Public Offices (1893)

The following year, Clark and Hutchinson won a contest for a new block of public offices for Ilford. Their design was not built, and seven years later, Ilford Town Hall was built under designs by architect Ben Wollard. Wollard's building is now used as the headquarters of the London Borough of Redbridge.

Littleborough library and offices (1894)

Clark and Hutchinson won another municipal contest in 1894, this time for a library and offices in Littleborough in Lancashire. A few years later, for whatever reason, the council decided not to go forward with the project.

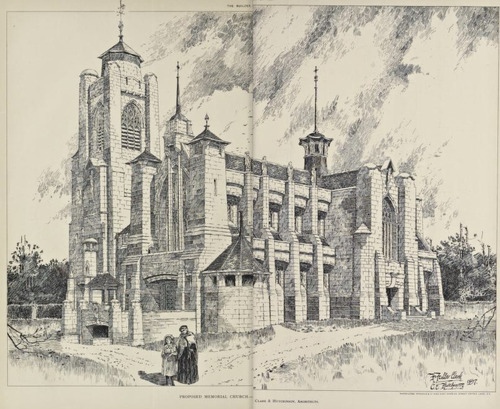

Preston memorial church (1895)

In 1895, Clark & Hutchinson unsuccessfully entered a competition to design a memorial church in Preston. They displayed drawings and plans for this church in 1897 at the RA.

St. Paul's Hospital (c. 1898)

In 1898, the St Paul's Hospital for Skin and Genito-Urinary Diseases opened at 13a Red Lion Square in Holborn. In 1904, Fuller Clark reported himself to be the "Honorable Architect" to that institution, though he omitted to mention that the hospital specialized in venereal diseases.

Given that he reported to be primarily engaged in hospital work in the early part of his career (having entered independent practice in 1893), it seems very likely that he contributed in part to the architectural work of the hospital. It is unknown to what extent.

Royal Mail Offices, Kingston (c. 1910)

Fuller Clark worked as a superintending architect under Lionel U Grace on the new offices (in reinforced concrete) of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company in Kingston. (Concrete and Constructional Engineering, 1910)

Kildare, St Andrew (c. 1912)

While in Jamaica, Fuller Clark also participated in the renovation of a Jamaican house called Kildare, in St Andrew Parish. This appears to be an old plantation house outside of Kingston.

Losing competition entries & work without materials

In his career, Fuller Clark entered a number of other competitions where he did not win or for I have not been able to find his entry. These included:

- Durham County Buildings (1895)

- West Ham Technical Institute (1895)

- Belfast City Hall (1897)

- Cartwright Memorial Hall (1899)

Fuller Clark also worked on the renovation of and additions to the following buildings. Unless otherwise specified, all projects were done in partnership with CE Hutchinson and in London. His handiwork unfortunately does not appear to be visible in any of the buildings below — many have since been renovated out of recognition or demolished entirely.

- 1897: Stables at 12 & 15 Gower Mews

- 1897: 45 Chandos Street

- 1898: 11 Westbourne Grove

- 1899: Excelsior pub, 153 Charing Cross Road

- 1899: 59 Christchurch Road

- 1900: 2 Alexander Mews (alone)

- 1900: The Mount, Duppas Hill Road, Croydon (alone)

- 1901: 66 Berners Street (with Percy A. Boulting)

- 1902: a bungalow in Halliford, Shepperton for a Mr James Parker Ayres

- 1913: 254 & 256 Romford Road (alone)

- 1924: Cemetery memorial, Wivenhoe, Essex (alone)